Angola's state hospital poor people assume is private

- Published

Oil-rich Angola has provided free public health care since its independence in 1975. But does the system favour the elite, asks Mayeni Jones.

Many residents of the Angolan capital Luanda have assured me that the Multiperfil clinic is private, and I can see why they would believe that.

The hospital is one of the best I have ever visited in sub-Saharan Africa.

The medical school has mock surgery rooms and wards stocked with the latest medical equipment.

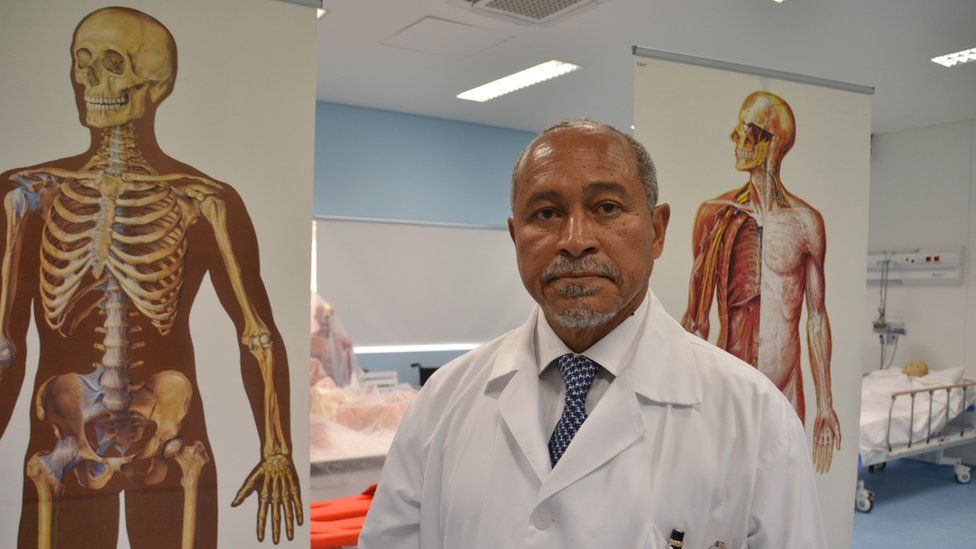

The hospital's director, Dr Manuel Filipe Dias dos Santos, tells me while showing me round that the hospital's record-keeping is completely electronic and that its doctors come from all over the world.

Multiperfil also trains medical students from across the country.

No ordinary mannequins

It's the summer holidays so the medical school is empty, apart from the human dummies that the students would practise on.

But these are no ordinary mannequins - we're told one of the most advanced ones costs up to $200,000 (£148,000).

"This mannequin," Dr Dos Santos tells me, "can cough, it can cry, it can speak, it can die. It can do anything a human being can do".

There's another reason why you might be forgiven for thinking this is a private clinic - patients here pay more than $200 as a down-payment before they can be attended to. A consultation costs almost $100.

These are huge sums for most Angolans.

Called away for a minister

But Multiperfil is not a private clinic. Built in 2002 with funds from a loan to the Angolan government, part of its revenue still comes from the state.

The clinic was granted special status by former President José Eduardo dos Santos, and is allowed to charge for care, despite being publicly funded.

It takes some lower income patients but the majority of the people it treats are insured politicians and members of the military.

And as in turns out, halfway through our tour, Dr Dos Santos is called away to personally tend to a government minister. Critics say this is a hospital that prioritises its elite clients.

Global health expert Sophie Harman from London's Queen Mary University says this is part of a trend in African public healthcare.

She has observed an increase in cases where insurance is used as a requirement in order to keep the general public out of certain hospitals.

As it is often a legal grey area, it is hard to hold people to account.

It also means that members of the public often don't realise that hospitals are public.

A 30-minute drive away from Multiperfil's orderly atmosphere, the situation is very different.

Syringes on sale

The Cajueiros General Hospital is in Cazenga, one of the city's most densely populated neighbourhoods.

As we arrive, a fight breaks out between relatives of patients and security. A guard reaches for his gun but stops short.

I got chatting to people who saw the beginning of the fight and they told me this a regular occurrence.

Relatives of patients often clash with security guards over the way they are treated. And that's not their only complaint.

One of those relatives, Justino, said his sister-in-law was having surgery inside.

"My family and I already spent the night out here yesterday and now I'm waiting for those who are inside visiting her," he said.

"One of us always has to be outside because sometimes the hospital staff come out with a prescription and we have to go and buy medicine because the hospital has run out."

Others told me that the cost of medicine is very high. A vitamin capsule can fetch up to 2,000 kwanza ($12; £9).

They're even asked to buy basic goods like gloves and syringes.

You can even buy some medical equipment from the hawkers outside the hospital.

Angola is going through a period of economic turmoil triggered by the global drop in the price of oil. The commodity constitutes 90% of the country's exports.

But before the collapse in oil prices, Angola was one of the world's fastest growing economies, with an average GDP growth of 11.1% from 2001 to 2010.

The problem is that the government did not invest in the health sector during its economic boom years, according to Anne Pitcher from Michigan University, who carried out a survey in Luanda on levels of satisfaction with the previous government.

Angola, which is recovering from a 27-year civil war, only spent an average of 4% of its GDP on health from 2004 to 2014. This is below the regional average of 6%, according to the World Bank.

"When we look at post-war countries, we often see that healthcare is one of the last thing to recover," explains Ms Pitcher.

"It requires a lot of investment but it also requires commitment by government and I think their investment in healthcare has not been what you would expect a middle-income country to have."

Impatient for change

Back at the Cajueiros hospital, families settle in for the night outside the hospital gates.

The ruling MPLA promised to increase investment in healthcare while campaigning ahead of last month's general elections.

As the new President Joao Lourenco starts his first term, Angolans will be looking to see whether he can fix an ailing and sick healthcare sector, despite the economic downturn.

That change can't come too soon for Catarina, whose sister is a patient.

"Many of us don't have money to put food on the table, let alone buy medication. What are we supposed to do?

"We need the government to invest in our hospitals so they have enough medicine because we can't afford it."

- Published25 August 2017

- Published22 August 2017

- Published13 August 2017

- Published21 June 2016

- Published21 February 2023